The Five Laws of Futurism

* I do not claim these are the only laws, or even that they are immutable. My aim is to provide a set of useful, basic tools that can be applied in any field to make informed decisions about the future. I appreciate any comments, questions, or outraged rants you have about it. - Will.

Laws are useful because they act as maps. The laws of physics tell us something should be true, even when we haven’t observed it yet. The laws of futurism are no different. Together, they present a guide to what lies ahead for civilization.

There are five laws worth knowing to forecast the future: Moore’s Law, Carlson’s Law, Metcalfe’s Law, Amara’s Law, and Gekko’s Law. The first two are based on technology, but have existed for a shorter time, making them less reliable. While they’re powerful forces driving innovation, they should be taken with a grain of salt. The last three laws stem from human behavior, and are likely to last as long as people exist.

1. Moore’s Law (increasing processing power)

Most people know Moore’s Law, which states that the number of semiconductors that can fit on a chip doubles roughly every two years.

This simple trend has led to most of the modern conveniences of the information age. One powerful example comes from Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson in The Second Machine Age:

“The ASCI Red, the first product of the U.S. government’s Accelerated Strategic Computing Initiative, was the world’s fastest supercomputer when it was introduced in 1996. It cost $55 million to develop and its one hundred cabinets occupied nearly 1,600 square feet of floor space (80 percent of a tennis court)...Designed for calculation-intensive tasks like simulating nuclear tests, ASCI Red was the first computer to score above one teraflop—one trillion floating point operations per second—on the standard benchmark test for computer speed.”

ASCI Red was surpassed in power in 2006 by another device, the Playstation 3, courtesy of Moore’s Law. Today, a high-end iPhone delivers 5 teraflops, almost three times as powerful as the government’s former juggernaut.

While Moore’s Law has allowed us to make electronics smaller, lighter, cheaper, and vastly more powerful with each passing year, it’s important to remember that it is not a law of physics. Unlike gravity, if we stop working on computation, Moore’s Law will cease. This is unlikely because of Gekko’s Law, which we’ll get to.

The other threats to Moore’s Law are the laws of physics themselves. At a certain point, heat and the speed of light become the enemies of progress, making it impossible for an infinite doubling of computer power. But there is strong evidence that this brick wall is still far away. Researchers at chip makers like ARM are designing 3D silicon wafers, and building purpose specific chips for functions like machine learning. Further out, they foresee supercooled chips and quantum chips picking up the slack.

While Moore’s law will end, we will likely swing like Tarzan to the next technological vine, and continue to improve computer performance.

2. Carlson’s Law (decreasing genetic sequencing cost)

Source: Wikipedia

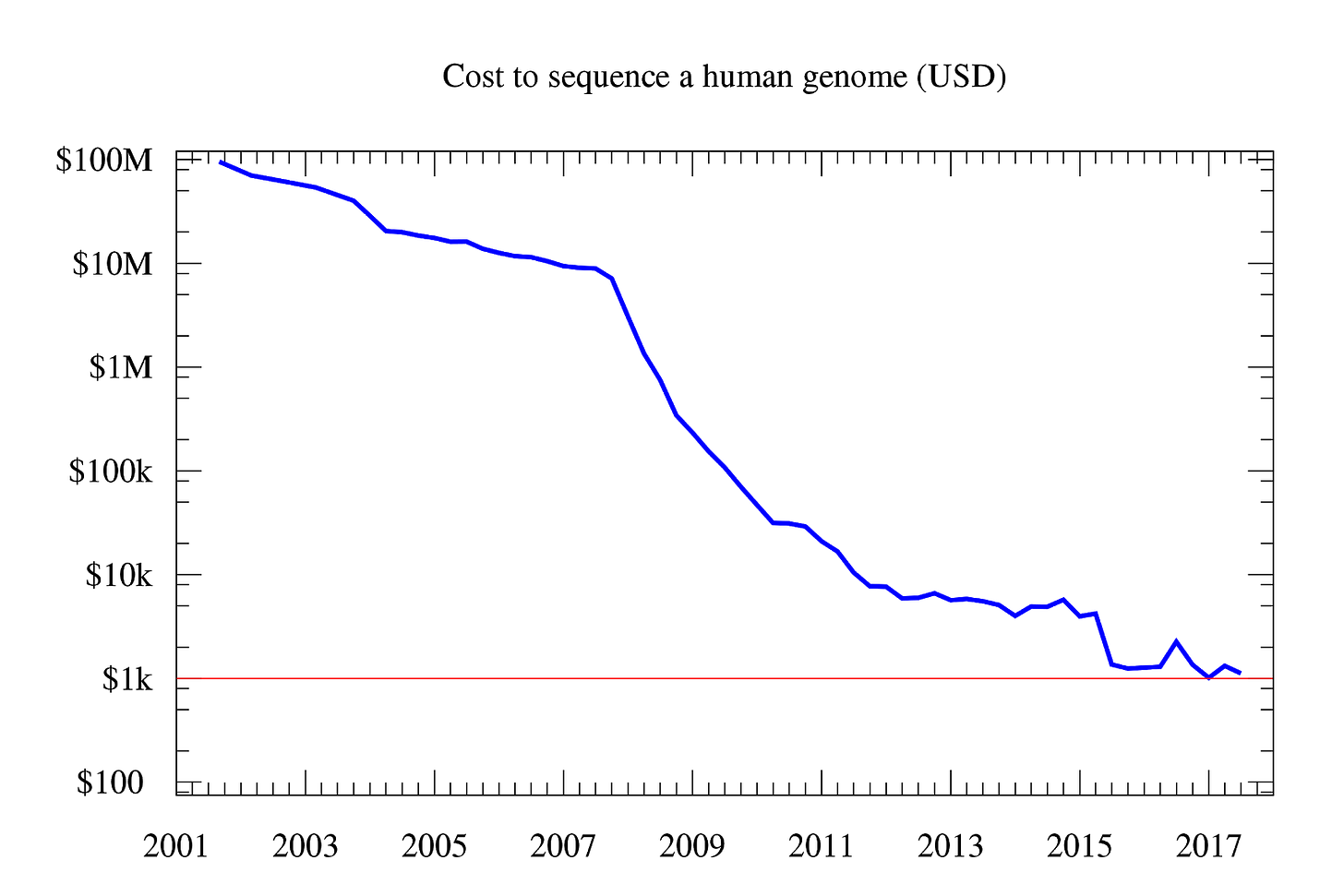

Carlson’s Law (it’s actually called the Carlson Curve, but it I’m sticking with law) is the biotech cousin of Moore’s Law, and is equally important. The curve shows the precipitous decline in the cost of gene sequencing (reading genetic code).

Gene sequencing is the gateway to a host of futuristic technologies, including gene editing methods like CRISPR/CAS9 (a protein) and TALENs (an enzyme). Research is underway to modify pig organs to aid the 114,000 people currently waitlisted for organ transplants in the U.S, improve the resurrect the wooly mammoth, and make humans resistant to radiation to enable safe space travel (four edits can make bacteria 100,000 times more radiation resistant). And all of these are projects from just one Harvard lab.

As the graph below shows, the rapid cost decline means biotech is advancing even faster than computation (although it piggybacks on advancements made by Moore’s Law).

The Carlson Curve predicts that gene sequencing will eventually be almost free. While it may still have a nominal charge, the way that flushing the toilet does, it will be equally quotidian. We may soon see certain people paid for the rights to their genetic code, as some mutations (like resistance to pain or extreme endurance) will become valuable modifications sold to the highest bidder.

Like Moore’s Law, the Carlson Curve is a recent phenomenon that will guide the direction of the future, although it may eventually fail. Given the size of the opportunity set (every living thing on Earth) it is unlikely we will exhaust its potential any time soon.

3. Metcalfe’s Law (big networks are strong networks)

We now leave the technological laws for the first behavioral law of the future: Metcalfe’s Law. Coined by Bob Metcalfe, the creator of Ethernet, the law states that “the value of a network is directly proportional to the square of the number of users connected to the system”. In other words, if you are the only person in a network, the value is 12 = 1, if you and a friend are in contact, the value jumps to 22 = 4, and so on. For much of human history, the value of our networks was limited by the Dunbar Number. This number, roughly 150, was suggested by anthropologist Robin Dunbar as the maximum number of meaningful connections a person can hold in their head. For this reason, most Neolithic villages were capped at 150. With the invention of writing, our networks could grow further, increasing the value of the human network as trade and information spread. Finally, in the information age, we smashed the Dunbar number with social networks and marketplaces like Uber. Uber would not be very useful if there were three drivers in New York, but it is immensely valuable with the over 100,000 drivers in the city today.

The more drivers there are, the easier it is to find a ride, encouraging more users to ride with uber over a competitor like Juno. This influx of riders encourages more drivers to join, further strengthening the network and entrenching Uber as the incumbent. The same network effects can be seen in Amazon, iOS, and Facebook. At a certain point, the network effect grows so strong that it is more advantageous to be part of the network than not. As evidenced by the recent furor over big tech in Congress, Metcalfe monopolies grow hard to break.

Metcalfe himself suggested that at large numbers, the value of the network is actually n(logn), meaning that networks grow quickly before leveling off in value. This has been empirically shown with the value of Facebook (blue) and Bitcoin (red):

Source: Bitcoin Spreads Like a Virus, Timothy F. Peterson, CFA, CAIA

Metcalfe’s Law is useful for forecasting because if you can spot a system that attracts and connects users, you can make a reasonable inference about its future value and success.

4. Amara’s Law (believe the hype, just not yet)

Futurist Roy Amara stated:

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run”.

This observation holds pretty much anywhere it is applied. Artificial intelligence research is one example. When the first AI breakthroughs were made in the 1950s, a wave of excited investment followed. In 1970, Marvin Minsky declared “from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being”. Several years later, funding dried up as research failed to deliver a convincing chess-player, let alone a human-equivalent machine. Processing power, data sources, and theoretical work could not match this grand vision. AI funding regained strength in the 1990s, and excitement again peaked in 1997 when IBM’s Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov, who was at the time the highest ranked chess player in the world. Funding collapsed again with the dotcom bust, and finally picked up again in 2012 when a team led by Geoffrey Hinton used deep learning to set a new record in Stanford’s ImageNet competition.

Looking back, it’s easy to see this as a series of booms and busts with little real gain. But beneath the frenzy, real progress has been made. Our current AI would be shocking to the researchers in the 1950s. Similarly, our near-term expectations are likely far overblown. Few AI researchers believe we will have generally intelligent machines in the next ten years, but Amara’s law makes them confident about predicting radical advances in the next hundred.

5. “Gekko’s Law” - Reliable Selfishness

In Iceland, huddled around an abandoned WWII airstrip, a collection of warehouses uses more electricity than all of the country’s home’s combined to mine Bitcoin. Worldwide, bitcoin mining uses roughly as much energy as Denmark, making it more energy intensive than some forms of actual mining. This is an example of principle I call “Gekko’s Law”.

Unlike Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko, I don’t believe “greed is good”, but that greed (selfishness) is dependable. People tend to do what maximizes their personal gain.

Gekko’s Law: “selfishness is reliable”, applies to everything from colonialism and climate change to bitcoin and AI.

Classical economists believe in rational choice theory, the concept that humans act out of rational self-interest to maximize their happiness. Gekko’s Law claims that people act out of self-interest even when it is irrational in the long term.

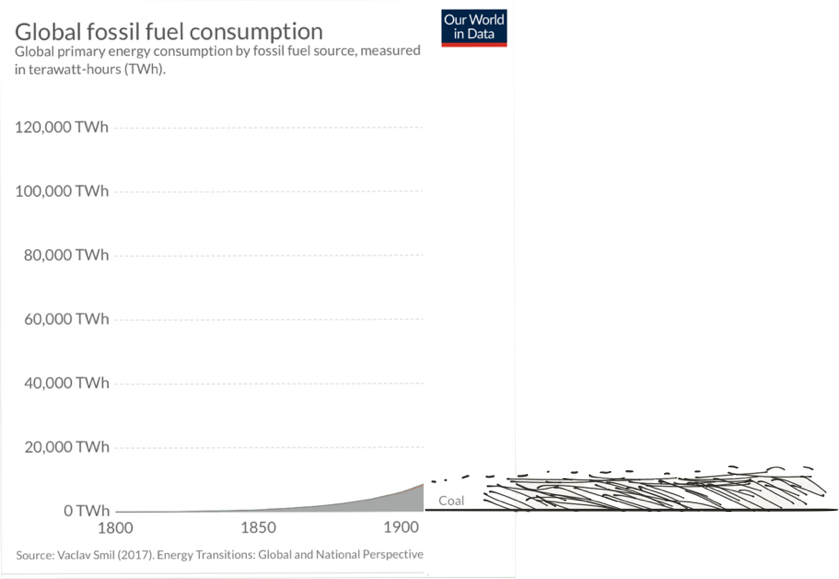

A classic example is climate change. We began to understand climate change in 1896, and if we had rationally extrapolated the model, we would have controlled fossil fuel use when it still looked like this:

We could have invested heavily in electric battery technology (invented in 1800). Instead, we failed stupendously, and our consumption now looks like this:

Like Bitcoin mining, this process is unsustainable, but shows few signs of stopping. Even though the players involved often acknowledge this, few are willing to change, and if they do, many are clamoring to take their place.

Gekko’s Law gets scary when combined with the other four Laws of Futurism. Take genetic engineering as an example. The payoff for gene therapies enabled by Moore’s Law and Carlson’s Law is astronomical. The gene replacement drug Zolgensma was approved by the FDA recently at a price of $2.1 million per dose. The proliferation of increasingly radical treatments using gene editing, synthesis (creating oligos, new strings of the DNA “letters” A,G,C, T), assembly (stitching oligos together) seems inevitable. Germline editing promises to sterilize the anopheles mosquito, ending malaria, and notorious experiments were recently conducted in China to create babies (supposedly) resistant to HIV. Massive potential markets and radical applications ensure that this field will continue to receive a flood of attention and investment.

However, this selfish rush for the next great thing also makes dangerous technology more accessible to terrorists. Imagine an airborne ebola virus that lived on surfaces for days, or genetic assassination viruses tailored to kill only a certain race or demographic. We can see these possibilities, but cannot resist the temptation to explore.

Gekko’s Law isn’t all bad though. As venture capitalists like Collaborative Fund show, predictable selfishness can be harnessed to make the world better. The trick is to make the new product or solution not only better for the planet, but better for the consumer, so that they will “selfishly” choose to do good.

Most people don’t drive a Tesla purely to help the earth (a bus is a greener form of transportation when you account for the production of lithium-ion batteries). Instead, people join the cult of Musk because driving a Tesla signals that you value design, care about the environment, and are generally cooler than someone who drives a Ford Fiesta (to all the Fiestistas out there, this is not personal). The Beyond Burger is climate activism disguised as healthy meat, and CloudKitchens is democratized cooking masquerading as convenient cuisine. Health and environmental sectors present the most obvious examples of positive Gekko’s Law, but the strategy can be applied to any vertical.

Putting the Five Together

We cannot control the Five Laws of Futurism, but we can use them to forecast and prepare for the road ahead. Each of them is valuable but limited on its own, but together they provide a powerful framework. While no credible future projection can be more than a collection of estimates, the laws give these projections a direction. Combine specific knowledge with an understanding that the world will be faster, cheaper, smarter, more surprising than it was today, and anticipate the self-interest of others, and you’ll have a better idea of the future than most.